Cite as: The Honorable Theodore V. Morrison, Jr., Lewis F. Powell, III & Thomas W. Merrill, Deregulatory Takings and Breach of the Regulatory Contract, 4 RICH. J. L. & TECH. 2 (Fall 1997), <http://www.richmond.edu/~jolt/v4si/speech2.html>.[**]

{1} The October 1996 issue of the New York University Law Review includes a work dealing with deregulatory takings and breach of deregulatory contracts. Next October, the N.Y.U. Law Review will contain a rebuttal, a response critiquing work done by J. Gregory Sidak and Daniel Spulber. This critique is coauthored by William J. Baumol and Thomas W. Merrill. We are very fortunate here today to have that same Thomas W. Merrill with us. Our participants this afternoon on the panel will go in that order. Lewis Powell will discuss the propositions that the Telecommunications Act, and perhaps other current proposals for restructuring the electric industry, will constitute either violations of the takings clause of the Fifth Amendment, a deregulatory contract or an implied contract, and perhaps other constitutional provisions such as the Due Process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. If he doesn't say that they do, he will probably raise serious questions as to whether or not they might do that.

{2} Lewis Powell is an attorney with the firm of Hunton & Williams. He has had extensive experience in this area representing GTE, which has already been mentioned and pretty well condemned here roundly by [comments drowned out by laughter]. I don't buy into that. I think GTE is perfectly within its rights to assert any constitutional protections it feels have been violated.

{3} Tom Merrill is the John Paul Stevens Professor of Law at Northwestern University and is counsel in the law firm of Sidley & Austin. He does consulting work for them with regard to the interests of AT&T, so he has two distinct interests represented here. Tom was born in Oklahoma. He was raised and attended college in Iowa and then received his law degree from University of Chicago. He lives in the Chicago area with his wife and three daughters. He has worked in the Department of Justice and the Solicitor General's office.

{4} I hope we will have a lively discussion between the two participants; we only have two, and I'm sure we will. But we've had these kinds of issues peripherally, maybe more directly than that before the commission. I don't want to be put in the position of asking questions because it might be interpreted as a point of view, and I don't want to risk that. So please, when we finish, we hope you'll have some time for some pretty pointed questions. Be as argumentative as you wish.

{5} Without further adieu, I give you Lewis Powell.

Lewis F. Powell, III

[*]

Partner, Hunton & Williams

{6} I thought it might be best to jump start my remarks with a Jeopardy question. The category is this: "Supposedly Knowledgeable, Supposedly Neutral, Telecommunications Regulator." The answer is: He recently said

We were told by President Clinton, Vice President Gore and the Congress to do three things:

1. Keep basic local prices frozen as solid as polar ice;

2. Lower long distance prices; and

3. Connect all classrooms and clinics.[1]

The question is: "Who is Reed Hundt?"

{7} I nearly drove into a ditch on Interstate 64 this morning when I heard Chairman Hundt say this on NPR. Freezing basic local rates as "solid as the polar ice" is the language that stuck most clearly in my memory. If incumbent local exchange carriers ("ILECs") want to summarize their problems with the FCC, they would need to look no further than the words of Chairman Hundt himself. Notably absent from his pithy list of objectives is any mention of universal service or of just compensation for LECs.

{8} I would submit to you, moreover, that Chairman Hundt's attitude appears to have infected the entire process of the FCC's attempted implementation of the Act - particularly as reflected in its ill-advised August 8, 1996 First Report and Order. Though its core pricing provisions were stayed by the Eighth Circuit in October 1996, the First Report and Order poisoned the well of public service commission deliberations in the arbitration process last fall.[2] Until state commissions can purge this poison, whether through self-help, or perhaps through medication prescribed by the federal courts, this is going to be a long and very contentious process.

{9} No doubt, Chairman Hundt's three objectives are politically quite popular. But one may reasonably ask, "Who is going to pay for this?" The economic stakes are huge. The policy implications are equally important, and it is now abundantly clear that ILECs will fight unlawful and confiscatory pricing to protect their legitimate property interests and universal service wherever necessary.

{10} As we all know, this is an acronym-rich environment. As an illustration of the perils of so-called "deregulation" and the inherent risks of a 5th Amendment taking, I would like to introduce a new acronym to the dialogue today. The acronym is "RIP." If you can endure a bit of suspense, I will tell you after a while what that acronym means.

{11} Hunton & Williams has been privileged to be among several firms called on by GTE to help it through the implementation of the Telecommunications Act. The process has been enormously arduous, not to mention expensive.

{12} The burdens have fallen widely. They have fallen particularly hard on state commissions, which were given almost no time in which to review reams of evidence about the costs involved and the prices that various participants in the arbitration process thought would be appropriate. One has to hope that over time, with more thoughtful deliberation -- both in state commissions and in federal courts -- the resulting prices will be more fair to local carriers and more sensitive to the universal service implications.

{13} In case it is not already painfully obvious to you, I am an advocate, not an academic. I have a client, and therefore a bias. I nonetheless submit that GTE and the other local exchange carriers have, by far, the more compelling arguments on the central pricing and policy issues raised by the Act. If these arguments continue to be brushed aside, ILECs will be the victims of massive deregulatory takings. The adverse consequences will not only befall ILECs and their shareholders, but local infrastructure will deteriorate for want of new investment, and universal service will be threatened.

{14}What exactly is a deregulatory taking? The article by Greg Sidak and Dan Spulber goes to great lengths to discuss the history of regulatory and deregulatory takings.[3] My new friend Tom Merrill has now published a response to the Sidak and Spulber piece. It's really not very complicated when you get right down to it.

{15} I will offer you some citations to the record of this proceeding here today. Even Professor Merrill seems to acknowledge the existence of the risk. In footnote 44 on page 1049 of his article, Merrill says,

{16} In this new world of local exchange service competition, if prices for network elements and access are set at confiscatory levels then some LECs may suffer, indeed some may even go out of business. But if this happens, others will immediately step in to take their place. Any constitutional infirmities and pricing levels can be rectified by an action for damages after the fact without jeopardizing public services.[4]

{17} My second citation is to a document that I submitted for your reading pleasure. It is the Complaint that GTE filed in federal court in Richmond against AT&T, MCI and the Virginia Commissioners, in their official capacities, I hasten to add.

{18} In the wake of the Virginia State Corporation Commission's resolution of the arbitration late in the fall of 1996, GTE felt obliged to file a federal lawsuit, suing the Commissioners in their official capacities, as well as the long distance carriers. GTE alleged the prices that the commission had set were confiscatory - exactly the kind of prices about which Tom Merrill spoke in footnote 44 of his article. The loop is the central element of the network. It's the wire that runs from your house to the phone company's central office. GTE sought a loop price of $36 a month. The commission set a loop price of only $19.16. The commission made a decision with respect to the wholesale discount. The wholesale discount is a wholesale price at which GTE will be obligated to sell retail services to long distance carriers. GTE currently offers these retail services only to its end users. The wholesale discount the commission chose was considerably larger than that advocated by GTE. If these decisions remain undisturbed, GTE is going to lose an enormous amount of money.

{19} The last citation I'll give you is to our prayer for relief which you will find on the very last page of our Complaint. We asked the federal court to declare that GTE is entitled to a competitively neutral, non-bypassable end user surcharge to cover GTE's stranded costs. Stranded costs are those costs left uncovered as the result of a deregulatory taking. [Stated another way, those are costs that are not covered by new prices that follow regulatory action changing the rules in the middle of the game.] Stranded costs take several forms. First and foremost, perhaps, the local carriers - GTE and the Bell Companies - have invested billions of dollars in the local telephony network. This investment was predicated on the old understanding within the regulatory framework that the LEC would recover those actual costs. Pricing such as that imposed by the Virginia Commission will fall short of allowing LECs to recover these huge expenditures.

{20} There's another facet of stranded costs that may also prove significant -- ongoing and future costs. The ILECs, after all, have statutory obligations to maintain and upgrade the existing networks. As the so called "carriers of last resort," they bear the lion's share of the universal service burden. Those costs are going to be substantial.

{21} Third, stranded costs may very well include the huge internal, implicit subsidies that currently exist in the rate structure. The basic residential rate is way below the actual cost to Bell Atlantic of running and maintaining the wire out to my house in rural Hanover County. The shortfall is covered by other services which are priced well above cost. Most state commissions neglected to protect or replace those revenue sources in last years arbitration decisions. Absent comprehensive rates rebalancing to allow prices to reflect actual costs, a recovery mechanism must be implemented for LECs' huge subsidy costs.

{22} The LECs' position in all this is quite straight forward. They built the local network; they own it; they are required to maintain it and to upgrade it. Now, the Congress says LECs must share it with their new competitors. Well, that's fine so long as the pricing regime is compensatory. The problem for LECs like GTE is that, thus far most commission arbitration decisions have not been fully compensatory. Indeed, as our Complaint stated in full--in federal courts in Richmond and all over the country - the prices set have fallen far short of being compensatory. We therefore anticipate substantial stranded costs, which must be covered in some fashion or another.

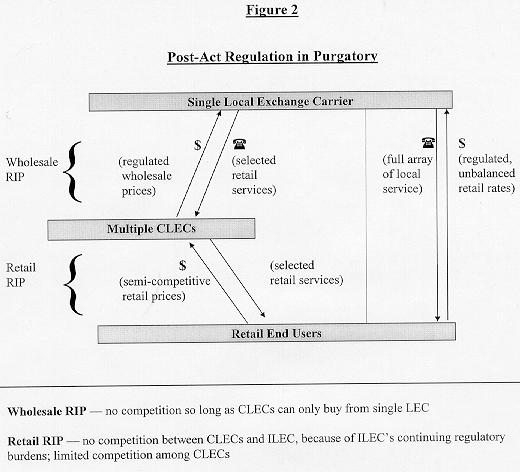

{23} So, where do we go from here? As I indicated, the substantial economic stakes will continue to drive this process forward. It will be a two-front battleground. The federal court actions are beginning. We are engaged in initial federal skirmishes regarding issues such as jurisdiction and ripeness, but sooner or later state commissions across the country are going to "approve" interconnection agreements reflecting the arbitrated terms. At that point, these federal complaints will mature and GTE and other ILECs will begin slugging it out with the long distance carriers in front of federal judges. At the same time, state commissions are going forward with their follow-up permanent costing and pricing inquiries. State commissions and the FCC will be addressing access charge reform and universal service. Consequently, the legal costs of this process will continue unabated and may even increase in 1997 and 1998.

{24} How then, should state commissions resolve these daunting challenges? You will not be surprised to learn that GTE has a solution in mind. First, the key to understanding is to focus on exactly where we will be once interconnection begins. The title of the operative chapter in the Act is "Development of Competitive Markets." The linchpin word, I would suggest to you, is not "competitive," but rather "development." The reality is that once interconnection begins, we will not be in a truly competitive environment. The "GTE proviso" that has attracted the attention of the long distance carriers is not a particularly surprising proviso when you think about it. We call these things interconnection agreements or interconnection contracts. Of course, it is not a contract in the sense in which we, as lawyers, are accustomed. It is not a voluntary meeting of the minds. It is something that the local carriers are being forced to do. Fundamentally, it is this element of governmental compulsion that implicates takings concerns.

{25} So if we will not be in competition, where will we be? My new telecommunications acronym, RIP, says it all - we will be mired for some time in Regulation in Purgatory. The new Act creates an enormous regulatory burden - hardly consistent with free and unfettered competition. Indeed, some have said they thought that the Congress should perhaps have put a time line on the new Act, and that it should have a 15-year sunset provision. The next decade and a half has been referred to as the "interim regime."

{26} In addition, Tom Merrill said it was important to seize the linguistic high ground. Competition, of course, is good. It makes us feel warm and fuzzy; we like competition - it is very American. Monopoly is bad, so monopolists must be flushed out and reformed. The mind set is that if the process of reformation is crippling, so be it. Capitalism is relentlessly dynamic and, therefore, inherently messy.

{27} Long distance carriers are cleverly telling America that they will bring us competition. The ads are already being run all over the country. Note that we have been bamboozled into calling AT&T, MCI, Sprint and others the Competitive Local Exchange Carriers, or CLECs. Well, let's take a look at this and see whether CLECs and the new Act will truly bring us competition as they promise. I assert that they will not, at least not for a long time.

{28} Let's consider one important area of the landscape that looms ahead - resale. As you know, the Act contemplates entry into the local market through two routes. Long distance carriers can lease bits and pieces of the local network, one element at a time, and then form a new platform for service by either combining leased elements with CLEC-provisioned facilities, or reassembling all the elements into their original configuration. In the alternative, long distance carriers can purchase from the LECs the full retail service, but at a wholesale discount, and then resell it to former LEC customers, presumably at a price lower than the LEC's tariffed retail rate. Let's examine resale for a moment.

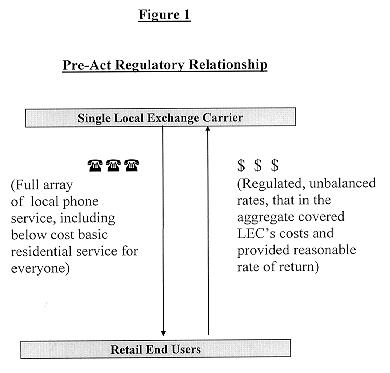

{29} As for telecommunication conditions prior to the Act, no wholesale level existed. A single ILEC (the awful monopolist) had a straight line to the retail end users. State commissions stepped in to protect the retail end users. Significantly, and this is often overlooked in the stampede toward competition, the commissions also had to set all rates sufficient to cover the ILECs' costs and provide a reasonable rate of return to each ILEC and its investors.

{30} Such was the state of affairs prior to the Act. It was very straightforward and uncomplicated. One local exchange monopolist served all the retail end users, with no wholesale intermediary. Rates were regulated, but hugely unbalanced in order to maintain low, uniform prices for basic phone service and protect the financial viability of the LEC.

{31} We are now headed to Regulation in Purgatory in the resale context. Under the resale RIP regime, the ILEC is required to sell to CLECs the same retail services that the ILEC offers to its end users, but at a regulated, wholesale discount. I call this new market segment the "Wholesale RIP." The CLECs will turn around and resell those services to retail end users, in "competition" among themselves and with the ILEC, which of course will continue to have a retail market. I call this segment the "Retail RIP."

{32} You can call this new alignment whatever you like under the statute, but it is not competition as economists understand it. At the newly-created wholesale level - the Wholesale RIP - the ILEC will not voluntarily be selling these services to CLECs. It is a forced sale. CLECs, of course, can only shop at the lone incumbent's store, so the new wholesale prices will be fixed by the regulators. At the retail level, CLECs will not have any regulatory restraints on the prices that they may charge to end users, but the ILEC will remain tightly yoked by regulated prices and continuing regulatory obligations - most notably, universal service. So whenever someone suggests that the Act will introduce competition through resale, I would submit to you that they are mistaken. Instead, the Act has consigned us to languish for many years in Regulation in Purgatory.

{33} Thus, the first part of reaching a solution is understanding that we are not moving immediately into a freely competitive environment. What, then, are the actual components of the solution? The challenge is for commissions and federal courts to interpret the Act in a way that is true to the Act's purpose and that avoids constitutional problems. This can be done without raising the specter of deregulatory takings, but doing so requires a comprehensive solution.

{34} First, the prices at which CLECs are permitted to lease pieces of the ILEC's network must be fully compensatory. They must be based on the ILEC's actual costs in the state in question, not the costs of some hypothetical, as yet unbuilt, network or the costs yielded by some proxy model. Similarly, the wholesale discount must be predicated on the retail costs an ILEC will in fact avoid through the new regime rather than on assumptions that the ILEC will either abandon the retail market or achieve substantial savings.

{35} Second, commissions must devise and implement a universal service funding solution simultaneously with implementation of the Act's other provisions. Universal service provides state commissions with a terrific opportunity to solve much of this problem. Universal service, properly restructured and funded consistent with the requirements of the Act, can help achieve the laudable objectives of the Act and do so on a competitively neutral basis. Without a simultaneous universal service solution, cost-based pricing for network elements and resale will inevitably strand substantial portions of the ILECs' historic and future investment. Not only would this situation create unnecessary legal issues, it would also degrade the network and cause deterioration of services to end users. Surely, the Congress could not have intended such a result.

{36} Another element of a comprehensive solution would be rate rebalancing. To go back to Tom Krattenmaker's admonition to take care with our choice of words, we could say "Let's have honest rates for a change. Let's have customers pay their fair share of the cost of the services they use." The needs of those massive universal service funds could be shrunk considerably if we had genuine rate rebalancing.

{37} Changing the rules is fine, so long as reasonable investments made under the old regulations are not stranded.

Thomas W. Merrill [*]

John Paul Stevens Professor of Law, Northwestern University

{38} Thanks, I appreciate the chance to come and speak to you today. Lewis told you that the constitutional issues are not terribly complicated. In support of that he pointed to the Sidak and Spulber article[5] which is 150 pages long. I would point out that the article does not even discuss the intricacies of the Telecommunications Act.[6] He then cited footnote 44 on page 23 of my article[7] and pages 34 and 65 of GTE's complaints.[8] With all due respect, I think I would say that in fact it is somewhat complicated. The constitutional issues raised by the Telecommunications Act are difficult questions; in many cases questions of first impression that have not been addressed in any meaningful fashion by any court in this country at any level. The application of those principles is also going to be a difficult one, and one that is going to have to be sensitive to the nuances of the telecommunications industry and to the specifics of the Telecommunications Act.

{39} We also heard a lot about Regulatory Purgatory, "RIP", and so forth. I will submit that overlaying the system of forward-looking pricing, which the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and many State Commissions have endorsed, with a series of hearings based on takings principles which have not yet been defined, is not a way to get us out of Regulatory Purgatory. Rather, it will send us straight to Regulatory Hell. So I guess in those points we are in disagreement.

{40} Why do I say this is constitutionally complicated? Because we are in essentially uncharted waters here as to what the constitutional principles might be that would apply to these cases. GTE and other Incumbent Local Exchange Carriers (ILECs) that have raised the constitutional questions have relied on the Supreme Court's takings cases in the public utility area. The Supreme Court had held for over 100 years that the takings clause applies to public utility rate-making.[9] But the regulatory schemes involved in these decisions are all very different from what we have in the Telecommunications Act in at least one very fundamental respect. These schemes all pre-suppose a situation of a public utility operating in a natural monopoly environment, where the main determinant of the stream of revenues that the company is going to earn being the rate order that the Public Utilities Commission establishes for it. It is not an easy process, but in this situation at least you can take the rate order and make some kind of prediction or extrapolation from the rate order to determine the revenues that the utility is likely to earn. You can then use that revenue stream as a basis for calculating whether or not the shareholders have been asked to assume an undue burden.

{41} Under the Telecommunications Act, in contrast, there is some regulation of rates that takes place. However, we are now talking about carrier-to-carrier rates for specific unbundled network elements or for services to be resold from wholesale rates or access charges, and so forth. The actual prices that the communications carriers charge to customers (once the Act is fully implemented) will not be subject to regulation but will be determined by competition. Under the Telecommunications Act there is no direct relationship between any of these regulatory rate setting actions and the final revenue stream. This relationship is the critical variable to ascertain to do any sort of takings analysis. In that respect I think the old cases are very different. I don't think they are irrelevant; I think we can extrapolate some useful principles from them. Nevertheless, we have to do some extrapolation. We can't simply apply them wholesale.

{42} Sidak and Spulber have also spoken at great length about what they have called the regulatory "contract" or compact.[10] There has been some attempt, although not so much in actual litigation under the Telecommunications Act, to invoke this breach of contract idea as a basis for restricting the pricing provisions used to implement the Telecommunications Act. However, the regulatory contract idea, or at least the authority for it, is also not directly apposite. Again, we have to do many heroic extensions from older cases. Most of the Supreme Court cases that would be applicable are the cases from between the 1890's and 1920's that involve city franchise agreements.[11] Typically, the city had one company that provided gas lighting, and then the city terminated that franchise and put in a franchise for electric lighting. Those cases arise in a very different context than what we are talking about here. The more recent Winstar decision,[12] which is often spoken about, also arises out of a different industry (the savings and loan industry) and involved a very recent promise that was well understood by everyone. The decision was clearly abrogated by the government and this had immediate and severe financial consequences. Again, the case is factually distinguishable from the situation we have here, so we have to extrapolate rather heroically from these other authorities in order to find out what the principles are that apply.

{43} Another complicating factor the Telecom Act regime sets up is a very complicated federal mechanism. Somebody suggested this morning that it may violate the Tenth Amendment, and there may be some merit in that suggestion. The Act proceeds with the general framework set up by the Congress. This is then implemented by regulations issued by the FCC; then it goes to the State Commissions for particular pricing decisions. It then goes back to federal district court, and who knows who is going to enforce the implementation of the whole thing. All this morning's speakers emphasized these peculiarities. Think of how that complicates any kind of takings or breach of contract analysis. Who do you sue, and when do you sue them? Arguably, if this is a taking, GTE should have sued the United States government as soon as the Act was passed. It was the United States Congress, I believe, which abrogated any exclusive territorial understandings which mandated competition and so on and so forth. If the gravamen of the complaint goes to those elements, perhaps the time when the suit should have been filed has already passed. Do you sue the FCC because of its pricing regulations? Perhaps you do, but then the courts may decide that the issue is premature since the pricing rules haven't been applied yet. Do you sue the State Commissions? Well, perhaps you do, but the State Commissions can always say "Well, we're just following federal law, so it's really not us that's doing this, it's the Feds that are making us do it." The federalism dimension complicates the issue and makes it difficult to know exactly when and how the takings analysis or the breach of contract analysis applies here.

{44} What are the constitutional principles that ought to apply in resolving these allegations? It is a lot easier to say what they're not than what they are. Let me suggest a few things about what they are not. One thing that neither the Fifth Amendment nor the regulatory contract idea supports is the notion that utilities like GTE or other ILECs have a of guaranteed right to the continuation of the revenue stream that they enjoyed under the prior system of regulation. There are passages in Sidak and Spulber that suggest that this is in fact some kind of constitutional entitlement. But that just can't be. The whole system of utilities regulation that we have had for decades in this country is premised on the idea that monopoly pricing can be legitimately regulated and that we can try to eliminate any pricing based on monopoly power above what a hypothetical competitive marketplace would generate. To the extent that the existing prices that utilities are charging contain monopoly or super-competitive elements, it is obviously legitimate for the government to reduce the revenue stream to that extent.

{45} The other thing we know is that if a utility suffers losses because of competition which comes about through technological change, there is no constitutional complaint that can be made. There are several old cases involving turnpike companies, for example, that go out of business because the railroad comes along.[13] Other cases discuss the street electric railway company that goes out of business because people start driving cars and taking internal combustion buses.[14] It is pretty clear from these cases that if a utility goes out of business because it is in a business which has become obsolete, then there is no constitutional infirmity there. Now, I am not suggesting these cases apply perfectly in this context; there are some distinctions. However, the proposition suggested in these cases that there is some kind of constitutional entitlement to the existing revenue stream is erroneous.

{46} The third thing we know for sure is there is no Constitutional right to a particular rate-making methodology. There is a lot of language in the GTE complaint and elsewhere claiming that somehow their real or actual costs have been ignored. What that really means is that the historic costs, the original depreciated costs of a plant that they acquired, is something that they are constitutionally entitled to recover. That is just not the case. The Supreme Court has said quite clearly that the Fifth Amendment takings clause is, in effect, neutral as between rate making methods.[15] If regulators want to adopt the old fair value approach, or if they want to adopt forward looking costs; there is nothing in the Constitution that prevents that from happening. I don't think that there is any constitutional entitlement to recover historic costs.

{47} What the Constitution, in fact, does require is much more difficult to say. I think the way I would extrapolate from the cases--this is an extrapolation we cannot know for sure--is that what is required is the opportunity to earn a competitive return on investment in regulated assets. I think this extrapolation is being very generous to the ILECs. The rate of return on investment should be determined by looking at investments of roughly comparable risk in the marketplace and setting a return on investment according to that benchmark. I think there is language in three or four of the Court's cases suggesting that this is the correct constitutional standard. I also believe that one can extrapolate from that standard to the present context without too much difficulty. Obviously, applying the standard is something else and raises many difficult questions.

{48} Is the Telecommunications Act unconstitutional under this competitive return standard? The answer: I don't have any idea. You don't either, and neither does Mr. Powell. The problem is, what are the revenues that will be earned on regulated assets under the new regime? There are simply too many unanswered variables to be able to tell at this point.

{49} One problem is stranded investment claims. People that raise these constitutional claims always bring up the nuclear power plants and most, true to form, talk about the Long Island Lighting Company (LILCO) plant. Now, I'd be the last person to say that a system of competitive access that stranded a bunch of nuclear power plants would not raise any constitutional questions. I think it probably would raise very serious constitutional questions, but that does not mean that there are any nuclear power plants out there in the local telephone exchange industry. In fact, it's not clear at this point in time that there will be very many, if any, stranded plants. One problem is that if competitors rent facilities from local companies, as opposed to building new facilities, there won't be a stranded plant. The plant in that situation is either going to be used by the ILEC, or it's going to be rented to a Competitive Local Exchange Company (CLEC). Either way, it is not stranded; somebody is using it. And if the rental prices are fair, as we think the forward-looking pricing of Total Element Long-Run Incremental Cost (TELRIC) is, then there won't be a stranded plant problem to that extent.

{50} Another problem is that there is tremendous growth and demand for local telephone service right now, as you all know. New services like Internet access, and perhaps video dial-tone in the near future, are going to stimulate consumer demand even more. It is possible that the loss in market share that competition creates will be offset by overall growth in the load on the system. Such an increase in system use will prevent stranded plants.

{51} Finally, some of the telephone plant is fixed and immobile, like local copper wire loops. However, some of it is re-deplorable to other applications or perhaps to other companies. It's not like there is a nuclear power plant that you can't pick up and move from one state to another, and can't convert into something else. So you have got some questions about the magnitude of stranded plant.

{52} Then you have questions about revenue sources. You can't just focus on the prices charged for carrier-to-carrier access or for unbundled network elements or for purchases at wholesale for retail. That's just a small part of the picture. You also have to look at other things. You have to look at the inter-exchange access fees about which the Commission is ready to issue some major regulatory proceedings. You have to look at the universal access charges that we have heard so much about. These are sources of revenue that have to be factored into the equation to determine what the total revenue picture for the ILECs is going to be after the Act is implemented.

{53} Additionally, I would submit that, at least to a degree, we have to look at some new sources of revenue that ILECs will gain access to, as a quid pro quo for local competition. The whole act is structured as a sort of large bargain whereby the ILECs submit to competition in the local arena. In return, the line of business restrictions are lifted, and they get into equipment manufacturing and inter-exchange service. To some extent the revenues that they can earn by getting in to these other markets are attributable to the regulated local plant because of network externalities. Those additional revenues ought to be counted into the equation too.

{54} Finally, we don't know what the revenues are going to be because we have to look at some imponderables, such as consumer loyalty and how much consumers are going to value one-stop shopping. In the end, the revenues are really a function of how well the ILECs compete and what quality of service they provide.

{55} All of these things are things that we obviously cannot know at this point in time. Nobody really knows what the revenue impact of the statute will be. There are many reasons to think that in the telecommunications industry, as opposed to the electric utility industry, for example, the stranded plant problem may be much less severe and may be rather minor in the larger picture.

{56} All this leads to the one point that I hope you would take away from this and which has to do with the nature of the remedy here for the constitutional violations that are alleged. I think this is really the core of the difference between Lewis and me, or between GTE and the position of some of the competitive carriers. At what point in time are we going to do this analysis and what will the remedy be? GTE is effectively arguing that the constitutional analysis has to be done now, and it has to be done in such a way as to avoid the possibility of any constitutional takings or breach of contract argument arising in the future. I would submit to you that the correct answer is that the constitutional analysis should be done after the Act is fully implemented because only then will we know whether, in fact, there has been a constitutional violation. I would reinforce this point by suggesting that you look at the nature of the constitutional right at issue here. The constitutional right is not an absolute right of property, nor is it an absolute right to do business as a utility. There is no such thing. It is a right to just compensation if property is taken by the government. It is a right to be paid if the government decides it is necessary to take your property in the public interest. This right can be fully vindicated after the Act is implemented. We are not going to know whether or not that right has been violated until the Act is fully implemented. Moreover, it would be wrong to interfere with the implementation of the Act now by jiggering prices in order to avoid this Constitutional issue, if the effect of the jiggering would be to undermine the implementation of the Act and the achievement of the goals the Congress has set forth.

{57} It is really a basic principle of takings law that if the government declares the need to take property for the public interest or the public use, the government has a right to go ahead and do that, provided it is going to pay compensation after the fact. In this sense, GTE is really in no different situation from the owner of land who has the land taken for a highway, let's say, and the owner complains that too much land is being taken for the government's purpose and that this will force the owner out of business. The remedy in that situation is not to stop the construction of the highway, bring in the engineers to testify in court as to how much land it really needs, and let the court decide the issue. The remedy is to let the government complete the taking, complete the project as it sees fit; and then provide just compensation after the fact to the landowner. The same basic principle ought to apply under the Telecommunications Act. Most economists, the FCC, and most State Commissioners think we need forward-looking pricing in order to effectively implement the local competition provisions. They think that is consistent with Congress' purposes. Therefore, we should have forward-looking pricing, and we should go ahead and implement the Act on that basis. If it turns out there's a taking because forward-looking pricing and competition deprive the incumbent local carriers of a competitive return on their investment, then they should be compensated appropriately at that time. How should they be compensated? It is my personal view that the best thing would be for them to file suit in a federal claims court under the Tucker Act[16] against the United States Government and have the United States taxpayers pay for any takings that this Act happens to entail. That would spread the burden most widely and most equitably; it would insure that the purposes of the Act are not frustrated; and it would respect the full scope of the constitutional rights that the ILECs have at stake. Thank You.

[*] The Honorable Theodore Morrison, Jr. has been a member of the Virginia State Corporation Commission since 1989. His long and distinguished career in public service includes such positions as a Delegate to the Virginia General Assembly from 1968-1988 and the Chairman of the House Committee on Finance from 1984-1988.

[*] Lewis F. Powell, III is a partner with Hunton & Williams, in the Litigation-Antitrust and Alternative Dispute Resolution Team.

[*] Thomas W. Merrill is the John Paul Stevens Professor of Law at Northwestern University and counsel to Sidley & Austin, in Chicago. He specializes in the areas of constitutional and regulatory law. He is co-author, with William J. Baumol, of Deregulatory Takings, Breach of the Regulatory Contract, and the Telecommunications Act of 1996 (forthcoming in the New York University Law Review).

[**] NOTE: All endnote citations in this article follow the conventions appropriate to the edition of THE BLUEBOOK: A UNIFORM SYSTEM OF CITATION that was in effect at the time of publication. When citing to this article, please use the format required by the Seventeenth Edition of THE BLUEBOOK, provided below for your convenience.

The Honorable Theodore V. Morrison, Jr., Lewis F. Powell, III & Thomas W. Merrill, Deregulatory Takings and Breach of the Regulatory Contract, 4 RICH. J. L. & TECH. 2 (Fall 1997), at http://www.richmond.edu/~jolt/v4si/speech2.html.

[1] Interview by Nat'l Public Radio with Reed Hundt, former FCC Chairman (May 5, 1997).

[2] On July 18, 1997, the Eighth Circuit followed through and eviscerated the central pricing rules of the First Report and Order. See Iowa Utils. Bd. v. FCC, 120 F.3d 753 (8th Cir. 1997). More recently, the Eighth Circuit clarified its July 18, 1997 decision by vacating yet another crucial component of the FCC's plan to accelerate entry into the local markets, without regard for ILECs right to full and fair compensation. See id. at 820.

[3] J. Gregory Sidak and Daniel F. Spulber, Deregulatory Takings and Breach of the Regulatory Contract, 71 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 851, (1996).

[4] William J. Baumol and Thomas W. Merrill, Deregulatory Takings Breach of the Regulatory Contract, and the Telecommunications Act of 1996, 72 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1037, 1049 (1997).

[5] J. Gregory Sidak & Daniel F. Spulber, Deregulatory Takings and Breach of the Regulatory Contract, 71 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 851 (1996).

[6] Telecommunications Act of 1996, Pub. L. No. 104-104, Feb. 8, 1996, 110 Stat. 56 (was to be codified at 47 U.S.C. § 151 et seq.) (found unconstitutional by ACLU v. Reno, 138 L.Ed.2d 874 (1997)).

[7] William J. Baumol & Thomas W. Merrill (To be published in October 1997 New York University Law Review)

[8] GTE Complaint drafted by Hunton & Williams.

[9] See generally Duquesne Light Company v. Burasch, 488 U.S. 299 (1989) (holding that there was no unconstitutional taking by the State). See also U.S. v. Willow River Power Co., 324 U.S. 499 (1945), wherein a power company argued the United States made an unconstitutional taking by raising the water level of the St. Croix River.

[10] See Sidak & Spulber supra note 1.

[11] See generally Capital City Light & Fuel Co. v. City of Tallahassee, 186 U.S. 401 (1902). A company brought suit to enjoin a city from constructing and operating its own electric-light plant, see id.; A city contracted with a company for gas and gas lights and switched to electricity during the term of the contract, but the city refused to pay for the upkeep of the gas lights, St. Paul Gaslight Co. v. City of St. Paul, 181 U.S. 142 (1901); A city contracted for gas lighting for 25 years and then constructed an electric power plant to supply the city with electric lighting, Newport Light Co. v. City of Newport, 151 U.S. 527 (1894).

[12] U.S. v. Winstar Corp., 116 S.Ct. 2432, 135 L.Ed.2d 964 (1996).

[13] Covington & Lexington Turnpike Rd. Co. v. Sandford, 164 U.S. 578 (1896).

[14] Market St. Ry. Co. v. Railroad Comm'n., 324 U.S. 548 (1945).

[15] See Duquesne Light Company v. Burasch, 488 U.S. 299 (1989).

[16] 28 U.S.C. §

1491 (1994).