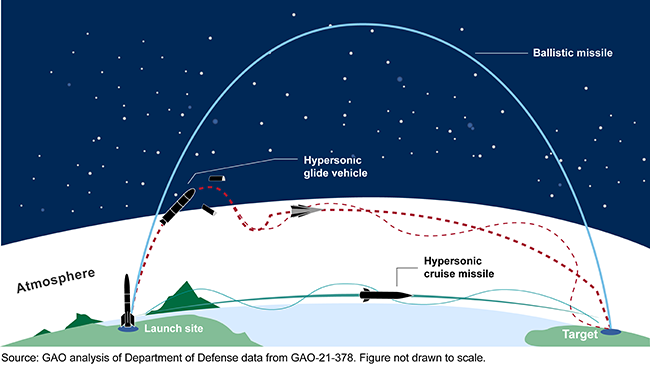

Hypersonic missiles present new challenges in nuclear deterrence, weapons regulation

By Joe Noser

When President Joe Biden and his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, met last week in San Francisco, the two leaders had lots to discuss: restoration of military communications, fentanyl controls, and climate change, to name a few.[1]

One issue that likely will not be on the table, however, is coming to a mutual understanding about regulating both nations’ hypersonic weapons programs.

.webp)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/3GRNHQR5N4N6VXU2H7MLK7WHAM.jpg)