By Christopher Cox*

* © 2020 Christopher Cox. Mr. Cox, a former U.S. Representative from California, is the author, and co-sponsor with then-U.S. Representative Ron Wyden, of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. He recently retired as a partner in the law firm of Morgan, Lewis & Bockius.

I. INTRODUCTION

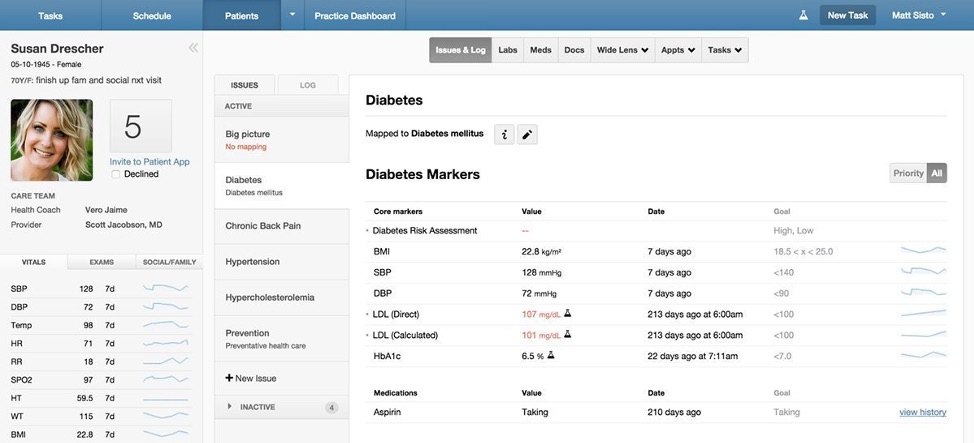

[1] Since 1996, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act[1] has governed the allocation of liability for online torts and crimes among internet content creators, platforms, and service providers. The statute’s fundamental principle is that content creators should be liable for any illegal content they create. Internet platforms are generally protected from liability for third-party content, unless they are complicit in the development of illegal content, in which case the statute offers them no protection.

[2] Prior to the enactment of Section 230, the common law had developed a different paradigm. New York courts took the lead in deciding that an internet platform would bear no liability for illegal content created by its users. This protection from liability, however, did not extend to a platform that moderated user-created content. Instead, only if a platform made no effort to enforce rules of online behavior would it be excused from liability for its users’ illegal content. This created a perverse incentive. To avoid open-ended liability, internet platforms would need to adopt what the New York Supreme Court called the “anything goes” model for user-created content. Adopting and enforcing rules of civil behavior on the platform would automatically expose the platform to unlimited downside risk.[2]

[3] The decision by the U.S. Congress to reverse this unhappy result through Section 230, enacted in 1996, has proven enormously consequential. By providing legal certainty for platforms, the law has enabled the development of innumerable internet business models based on user-created content. It has also protected content moderation, without which platforms could not even attempt to enforce rules of civility, truthfulness, and conformity with law. At the same time, some courts have extended Section 230 immunity to internet platforms that seem complicit in illegal behavior, generating significant controversy about both the law’s intended purpose and its application.[3] Further controversy has been generated as a result of public debate over the role that the largest internet platforms, including social media giants Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, play in America’s political and cultural life through their content moderation policies.

[4] The increasing controversy has led to numerous efforts to amend Section 230 that are now pending in Congress.[4] On one side of the debate over the future of the law are civil libertarians including the American Civil Liberties Union, who oppose amending Section 230 because they see it as the reason platforms can host critical and controversial speech without constant fear of suit.[5] They are joined in opposition to amending Section 230 by supporters of responsible content moderation, which would be substantially curtailed or might not exist at all in the absence of protection from liability.[6] Others concerned with government regulation of speech on the internet, including both civil libertarians and small-government conservatives, are similarly opposed to changing the law.[7]

[6] On the other side of the debate, pressing for reform of Section 230, are proponents of treating the largest internet platforms as the “public square,”[8] which under applicable Supreme Court precedent[9] would mean that all speech protected by the First Amendment must be allowed on those platforms. (Section 230, in contrast, protects a platform’s content moderation “whether or not such material is constitutionally protected.”)[10] Others in favor of amending Section 230 argue that internet platform immunity from suit over user-created content should come with conditions: for example, providing law enforcement access to encrypted data from their customers’ cell phones and computers,[11] or proving that they are taking aggressive steps to screen user-created content for illegal material.[12] Further support for amending Section 230 has come from opponents of “Big Tech” on both ends of the political spectrum, who are unhappy with the moderation practices of the largest platforms. Critics on the left complained, for example, that Facebook did too little to weed out Russian disinformation;[13] on the right, the Trump administration railed against “censorship” by social media platforms.[14] Both groups see Section 230 as unfairly insulating the platforms from lawsuits challenging their current moderation practices.[15]

[7] The sponsors of the several bills that have been introduced in both the House and the Senate during the 116th Congress (2019-21) to amend Section 230 have emphasized the original purposes of the law, while maintaining that court decisions and the conduct of the large internet platforms have distorted what Congress originally intended.[16] This has brought the history of Section 230’s original enactment into sharp focus, making the actual record of its birth and odyssey from idea into law relevant to both policy makers and courts. In this article, I recount the circumstances that led me to write this legislation in 1995, and the work that my original co-sponsor, then-U.S. Representative Ron Wyden (D-OR), and I did to win its passage. Finally, I describe how the original intent of the law, as interpreted in the courts during the intervening decades, has been reflected in the actual application of Section 230 to the circumstances of the modern internet.

[8] As will be seen, the intent of Congress — often an elusive concept, given the difficulty of encapsulating the motives of 535 policy makers with competing partisan perspectives — is more readily apprehended in this case, given the widespread support that Section 230 received from both sides of the aisle. That intent is clearly expressed in the plain language of the statute, and runs counter to much of the 21st century narrative about the law.

II. THE COMMUNICATIONS DECENCY ACT, S. 314

[9] It was a hot, humid Washington day in the summer of 1996 when James Exon (D-NE), standing at his desk on the Senate floor, read the following prayer into the record as a prelude to passage of his landmark legislation[17] that would be the first ever to regulate content on the internet:

Almighty God, Lord of all life, we praise You for the advancements in computerized communications that we enjoy in our time. Sadly, however, there are those who are littering this information superhighway with obscene, indecent, and destructive pornography. … Lord, we are profoundly concerned about the impact of this on our children. … Oh God, help us care for our children. Give us wisdom to create regulations that will protect the innocent.[18]

[10] Immediately following his prayer, Senator Exon found it had been answered, in the form of his own proposal to ban anything unsuitable for minors from the internet. His bill, as originally introduced, authorized the Federal Communications Commission to adopt and enforce regulations that would limit what adults could access online, and could themselves say or write, to material that is suitable for children. Anyone who posted any “indecent” communication, including any “comment, request, suggestion, proposal, [or] image” that was viewable by “any person under 18 years of age,” would become criminally liable, facing both jail and fines.[19]

[11] The Exon dragnet was cast wide: not only would the content creator — the person who posted the article or image that was unsuitable for minors — face jail and fines. The bill made the mere transmission of such content criminal as well.[20] Meanwhile, internet service providers would be exempted from civil or criminal liability for the limited purpose of eavesdropping on customer email in order to prevent the transmission of potentially offensive material.

[12] Like his Nebraska forebear William Jennings Bryan, who passionately defended creationism at the infamous Scopes “Monkey Trial,” James Exon was not known for being on the cutting edge of science and technology. His motivation to protect children from harmful pornography was pure. But his grasp of the rapidly evolving internet was sorely deficient. Nor was he alone: a study completed that same week revealed that of senators who voted for his legislation, 52% had no internet connection.[21] Unfamiliarity with the new technology they were attempting to regulate had immediate side effects. What many of these senators failed to grasp was how different the internet was from the communications technologies with which they were familiar and had regulated through the Federal Communications Commission for decades.

[13] Broadcast television had long consisted of three networks; and even with the advent of cable, the content sources were relatively few and all the millions of viewers were passive. Radio, likewise. For years there had been one phone company and now there were but a handful more. The locus of all of this activity was domestic, within the jurisdiction and control of the United States. None of this bore any relation to the internet. On this new medium, the number of content creators — each a “broadcaster,” as it were — was the same as the number of users. It would soon expand from hundreds of millions to billions. It would be an impossibility for the federal government to pre-screen all the content that so many people were creating all day, every day. And there was the fact that the moniker “World Wide Web” was entirely apt, since the internet functions globally. It was clear to many, even then, that most of the content creation would ultimately occur outside the jurisdiction of federal authorities — and that enforcement of Exon-like restrictions in the U.S. would simply push the sources of the banned content offshore.

[14] Above all, the internet was unique in that communications were instantaneous: the content creators could interact with the entire planet without any intermediation or any lag time. In order for censors to intervene, they would have to destroy the real-time feature of the technology that made it so useful.

[15] Not everyone in the Senate was enthusiastic about the Exon bill. The chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee, Larry Pressler, a South Dakota Republican, chose not to include it in his proposed committee version of the Telecommunications Act.[22] Vermont Senator Patrick Leahy, the ranking Democrat on the Judiciary Committee’s Antitrust, Business Rights and Competition subcommittee, opposed it for a prescient reason: the law of unintended consequences. “What I worry about, is not to protect pornographers,” Leahy said. “Child pornographers, in my mind, ought to be in prison. The longer the better. I am trying to protect the Internet, and make sure that when we finally have something that really works in this country, that we do not step in and screw it up, as sometimes happens with government regulation.”[23]

[16] But Exon was persistent in pursuing what he called the most important legislation of his career. He went so far as to lobby his colleagues on the Senate floor by showing them the hundreds of lewd pictures he had collected in his “blue book,” all downloaded from the web and printed out in color.[24] It made Playboy and Penthouse “pale in offensiveness,” he warned them.[25] The very day he offered his prayer, the Senate debated whether to add an amended version of Exon’s legislation[26] to a much larger bill pending in Congress.[27] This was the first significant overhaul of telecommunications law in more than 60 years, a thorough-going revision of the Communications Act of 1934. Though that overhaul was loaded with significance, the pornography debate — broadcast live on C-SPAN, then still a novelty — is what caught the public’s attention.

[17] During that brief debate, breathless speeches conjuring lurid images of sordid sex acts overwhelmed academic points about free speech, citizens’ privacy rights, and the way the internet’s packet-switched architecture actually works. The threat posed to the internet itself by Exon’s vision of a federal speech police paled into irrelevance. With millions of people watching, senators were wary of appearing as if they did not support protecting children from pornography. The lopsided final tally on Exon’s amendment to the Telecommunications Act showed it. The votes were 84 in favor, 16 opposed.[28]

III. THE INTERNET FREEDOM AND FAMILY EMPOWERMENT ACT, H.R. 1978

[18] When it came to familiarity with the internet, the House of Representatives was only marginally more technologically conversant than the Senate. While a handful of members were conversant with “high tech,” as it was called, most were outright technophobes quite comfortable with the old ways of doing things. Many of the committee chairs, given the informal seniority system in the House, were men in their 70s. They saw little need for improvement in the tried-and-true protocols of paper files in folders, postcards and letters on stationery, and the occasional phone call. The Library of Congress was filled with books, so there was no apparent need for any additional sources of information.

[19] On the day Exon’s bill passed the Senate, more than half of the senators (including Senator Exon) didn’t even have an email address.[29] In the House it was worse: only 26% of members had an email address.[30] The conventional wisdom was that, with the World’s Greatest Deliberative Body having spoken so definitively, the House would follow suit. And for the same reason: with every House member’s election just around the corner, none would want to appear weak on pornography. The near-unanimous Senate vote seemed dispositive of the question.

[20] While it is often the case that the House legislates impulsively while the Senate takes its time, in this case the reverse happened. As chairman of the House Republican Policy Committee — and someone who built his own computers and had been using the internet for years — I took a serious interest in the issue. After some study of Exon’s legislation, I had already decided to write my own bill, as an alternative. Fortuitously, I was a member of the Energy and Commerce Committee, which on the House side had jurisdiction over the Telecommunications Act to which Exon had attached his bad idea.

[21] One of the tech mavens in the House at the time was Ron Wyden, a liberal Democrat from Oregon whose Stanford education and activist streak (he’d run the Gray Panthers advocacy group in his home state during the 1970s) made him a perfect legislative partner. The two of us had recently shared a private lunch and bemoaned the deep partisanship in Congress that mostly prevented Democrats and Republicans from writing legislation together. We decided this was due to members flogging the same old political hot-button questions, on which everyone had already made up their minds.

[22] At the conclusion of our lunch, we decided to look for cutting-edge issues that would present novel and challenging policy questions, to which neither we nor our colleagues would have a knee-jerk response. Then, after working together to address the particular issue with a practical solution, we’d work to educate members on both sides, and work for passage of truly bipartisan legislation. It was not much longer afterward that the question of regulating speech on the internet presented itself, and Rep. Wyden and I set to work.

[23] Not long afterward, Time magazine reported that “the balance between protecting speech and curbing pornography seemed to be tipping back toward the libertarians.” They noted that “two U.S. Representatives, Republican Christopher Cox of California and Democrat Ron Wyden of Oregon, were putting together an anti-Exon amendment that would bar federal regulation of the internet and help parents find ways to block material they found objectionable.”[31]

[24] We named our bill the Internet Freedom and Family Empowerment Act, to describe its two main components: protecting speech and privacy on the internet from government regulation, and incentivizing blocking and filtering technologies that individuals could use to become their own censors in their own households. Pornographers illegally targeting minors would not be let off the hook: they would be liable for compliance with all laws, both civil and criminal, in connection with any content they created. To avoid interfering with the essential functioning of the internet, the law would not shift that responsibility to internet platforms, for whom the burden of screening billions of digital messages, documents, images, and sounds would be unreasonable — not to mention a potential invasion of privacy. Instead, internet platforms would be allowed to act as “Good Samaritans” by reviewing at least some of the content if they chose to do so in the course of enforcing rules against “obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable” content.[32]

[25] This last feature of the bill resolved a conflict that then existed in the courts. In New York, a judge had held that one of the then-two leading internet platforms, Prodigy, was liable for defamation because an anonymous user of its site had claimed that an investment bank and its founder, Jordan Belfort, had committed securities fraud. (The post was not defamatory: Belfort was later convicted of securities fraud, but not before Prodigy had settled the case for a substantial figure. Belfort would achieve further infamy when he became the model for Leonardo DiCaprio’s character in The Wolf of Wall Street.)[33]

[26] In holding Prodigy responsible for content it didn’t create, the court effectively overruled a prior New York decision involving the other major U.S. internet platform at the time, CompuServe.[34] The previous case held that online service providers would not be held liable as publishers. In distinguishing Prodigy from the prior precedent, the court cited the fact that Prodigy, unlike CompuServe, had adopted content guidelines. These requested that users refrain from posts that are “insulting” or that “harass other members” or “are deemed to be in bad taste or grossly repugnant to community standards.” The court further noted that these guidelines expressly stated that although “Prodigy is committed to open debate and discussion on the bulletin boards … this doesn’t mean that ‘anything goes.’”[35]

[27] CompuServe, in contrast, made no such effort. On its platform, the rule was indeed “anything goes.” As a user of both services, I well understood the difference. I appreciated the fact that there was some minimal level of moderation on the Prodigy site. While CompuServe was a splendid service and serious users predominated, the lack of any controls whatsoever was occasionally noticeable and, I could easily envision, bound to get worse.

[28] If allowed to stand, this jurisprudence would have created a powerful and perverse incentive for platforms to abandon any attempt to maintain civility on their sites. A legal standard that protected only websites where “anything goes” from unlimited liability for user-generated content would have been a body blow to the internet itself. Rep. Wyden and I were determined that good faith content moderation should not be punished, and so the Good Samaritan provision in the Internet Freedom and Family Empowerment Act was born.[36]

[29] In the House leadership, of which I was then a member, there were plenty of supporters of our effort. The new Speaker, Newt Gingrich, had long considered himself a tech aficionado and had already proven as much by launching the THOMAS project at the Library of Congress to digitize congressional records and make them available to the public online. He slammed the Exon approach as misguided and dangerous. “It is clearly a violation of free speech, and it’s a violation of the right of adults to communicate with each other,” the Speaker of the House said at the time, adding that Exon’s proposal would dumb down the internet to what censors believed was acceptable for children to read. “I don’t think it is a serious way to discuss a serious issue,” he explained, “which is, how do you maintain the right of free speech for adults while also protecting children in a medium which is available to both?”[37]

[30] Rep. Dick Armey (R-TX), then the new House Majority Leader, joined the Speaker in supporting the Cox-Wyden alternative to Exon. So did California’s David Dreier (R-CA), the Chairman of the House Rules Committee, who was closely in touch with the global hi-tech renaissance being led by innovators in his home state. They were both Republicans, but my fellow Californian Nancy Pelosi, not yet a member of the Democratic leadership, weighed in as well, noting that Exon’s approach would have a chilling effect on serious discussion of HIV-related issues.[38]

[31] In the weeks and months that followed, Rep. Wyden and I conducted outreach and education among our colleagues in both the House and Senate on the challenging issues involved. It was a rewarding and illuminating process, during which we built not only overwhelming support, but also a much deeper understanding of the unique aspects of the internet that require clear legal rules for it to function.

[32] Two months after Senator Exon successfully added his Communications Decency Act to the Telecommunications Act in the Senate, the Cox-Wyden measure had its day in the sun on the House floor.[39] Whereas Exon had begun with a prayer, Rep. Wyden and I began on a wing and prayer, trying to counter the seemingly unstoppable momentum of a near-unanimous Senate vote. But on this day in August, the debate was very different than it had been across the Rotunda.

[33] Speaker after speaker rose in support of the Cox-Wyden measure, and condemned the Exon approach. Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-CA), the mother of 10 and 13-year old children, shared her concerns with internet pornography and noted that she had sponsored legislation mandating a life sentence for the creators of child pornography. But, she emphasized, “Senator Exon’s approach is not the right way … it will not work.” It was, she said, “a misunderstanding of the technology.”[40] Rep. Bob Goodlatte, a Virginia Republican, emphasized the potential the internet offered and the threat to that potential from Exon-style regulation. “We have the opportunity for every household in America, every family in America, soon to be able to have access to places like the Library of Congress, to have access to other major libraries of the world, universities, major publishers of information, news sources. There is no way,” he said, “that any of those entities, like Prodigy, can take the responsibility to edit out information that is going to be coming in to them from all manner of sources.”[41]

[34] In the end, not a single Representative spoke against the bill. The final roll call on the Cox-Wyden amendment was 420 yeas, 4 nays.[42] It was a resounding rebuke to the Exon approach in his Communications Decency Act. The House then proceeded to pass its version of the Telecommunications Act — with the Cox-Wyden amendment, and without Exon.[43]

IV. THE TELECOMMUNICATIONS ACT OF 1996

[35] The Telecommunications Act, including the Cox-Wyden amendment, would not be enacted until the following year. In between came a grueling House-Senate conference that was understandably more concerned with resolving the monumental issues in this landmark modernization of FDR-era telecommunications regulation. During the extended interlude, Rep. Wyden and I, along with our now much-enlarged army of bipartisan, bicameral supporters, continued to reach out in discussions with members about the novel issues involved and how best to resolve them. This resulted in some final improvements to our bill, and ensured its inclusion in the final House-Senate conference report.

[36] But political realities as well as policy details had to be dealt with. There was the sticky problem of 84 senators having already voted in favor of the Exon amendment. Once on record with a vote one way — particularly a highly visible vote on the politically charged issue of pornography — it would be very difficult for a politician to explain walking it back. The Senate negotiators, anxious to protect their colleagues from being accused of taking both sides of the question, stood firm. They were willing to accept Cox-Wyden, but Exon would have to be included, too.

[37] The House negotiators, all politicians themselves, understood. This was a Senate-only issue, which could be easily resolved by including both amendments in the final product. It was logrolling at its best.[44]

[38] President Clinton signed the Telecommunications Act of 1996 into law in February at a nationally televised ceremony from the Library of Congress Reading Room, where he and Vice President Al Gore highlighted the bill’s paving the way for the “information superhighway” of the internet.[45] There was no mention of Exon’s Communications Decency Act. But there was a live demonstration of the internet’s potential as a learning tool, including a live hookup with high school students in their classroom. And the president pointedly objected to the new law’s criminalization of transmission of any “indecent” material, predicting that these provisions would be found violative of the First Amendment and unenforceable.[46]

[39] Almost before the ink was dry and the signing pens handed out to the VIPs at the ceremony, the Communications Decency facet of the new law faced legal challenges. By summer, multiple federal courts had enjoined its enforcement.[47] The following summer the U.S. Supreme Court delivered its verdict with the same spirit that had characterized its House rejection.[48] The Court (then consisting of Chief Justice Rehnquist and Associate Justices Stephens, O’Connor, Suiter, Kennedy, Thomas, Ginsburg, and Breyer), unanimously held that “[i]n order to deny minors access to potentially harmful speech, the CDA effectively suppresses a large amount of speech that adults have a constitutional right to receive and to address to one another. That burden on adult speech is unacceptable.”[49]

[40] The Court’s opinion cited Senator Patrick Leahy’s comment that in enacting the Exon amendment, the Senate “went in willy-nilly, passed legislation, and never once had a hearing, never once had a discussion other than an hour or so on the floor.”[50] It noted that transmitting obscenity and child pornography, whether via the internet or other means, was already illegal under federal law for both adults and juveniles, making the draconian Exon restrictions on speech unreasonable overkill.[51] And there was more: under the Exon approach, the high court pointed out, any opponent of particular internet content would gain “broad powers of censorship, in the form of a ‘heckler’s veto.’” He or she “might simply log on and inform the would-be discoursers that his 17-year-old child” was also online. The standard for what could be posted in that forum, chat room, or other online context would immediately be reduced to what was safe for children to see.[52]

[41] In defenestrating Exon, the Court was unsparing in its final judgment. The amendment was worse than “’burn[ing] the house to roast the pig.” It cast “a far darker shadow over free speech, threaten[ing] to torch a large segment of the Internet community.” Its regime of “governmental regulation of the content of speech is more likely to interfere with the free exchange of ideas than to encourage it.”[53]

[42] With that, Senator Exon’s deeply flawed proposal finally died. In the Supreme Court, Rep. Wyden and I won the victory that had eluded us in the House-Senate conference.

[43] One irony, however, persists. When legislative staff prepared the House-Senate conference report on the final Telecommunications Act, they grouped both Exon’s Communications Decency Act and the Internet Freedom and Family Empowerment Act into the same legislative title. So the Cox-Wyden amendment became Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act — the very piece of legislation it was designed to rebuke. Today, with the original Exon legislation having been declared unconstitutional, it is that law’s polar opposite which bears Senator Exon’s label.

V. CONGRESSIONAL INTENT IN PRACTICE: HOW SECTION 230 WORKS

[44] By 1997, with the Communications Decency Act erased from the future history of the internet, Section 230 had already achieved one of its fundamental purposes. In contrast to the Communications Decency Act, which was punitive, heavily regulatory, and government directed, Section 230 focused on enabling user-created content by providing clear rules of legal liability for website operators that host it. Platforms that are not involved in content creation were to be protected from liability for content created by third-party users.

[45] This focus of Section 230 proceeded directly from our appreciation of what was at stake for the future of the internet. As the debate on the Cox-Wyden amendment to the Telecommunications Act made clear, not only the bill’s authors but a host of members on both sides of the aisle understood that without such protection from liability, websites would be exposed to lawsuits for everything from users’ product reviews to book reviews. In 21st century terms, this would mean that Yelp would be exposed to lawsuits for its users’ negative comments about restaurants, and Trip Advisor could be sued for a user’s disparaging review of a hotel. Indeed any service that connects buyers and sellers, workers and employers, content creators and a platform, victims and victims’ rights groups — or provides any other interactive engagement opportunity one can imagine — would face open-ended liability if it continued to display user-created content.

[46] In the years since the enactment of Section 230, in large measure due to a legal framework that facilitates the hosting of user-created content, such content has come to typify the modern internet. Not only have billions of internet users become content creators, but equally they have become reliant upon content created by other users. Contemporary examples abound. In 2020, without user-created content, many in the United States contending with the deadliest tornado season since 2011 could not have found their loved ones.[54] Every day, millions of Americans rely on “how to” and educational videos for everything from healthcare to home maintenance.[55] During the COVID-19 crisis, online access to user-created pre-K, primary, and secondary education and lifelong learning resources has proven a godsend for families across the country and around the world.[56] More than 85% of U.S. businesses with websites rely on user-created content, making the operation of Section 230 essential to ordinary commerce.[57] The vast majority of Americans feel more comfortable buying a product after researching user generated reviews,[58] and over 90% of consumers find user-generated content helpful in making their purchasing decisions.[59] User generated content is vital to law enforcement and social services.[60] Following the rioting in several U.S. cities in 2020, social workers were able to match people with supplies and services to victims who needed life-saving help, directing them with real-time maps.[61]

[47] Creating a legal environment hospitable to user-created content required that Congress strike the right balance between opportunity and responsibility. Section 230 is such a balance — holding content creators liable for illegal activity while protecting internet platforms from liability for content created entirely by others. Most important to understanding the operation of Section 230 is that it does not protect platforms liable when they are complicit — even if only in part — in the creation or development of illegal content.

[48] The plain language of Section 230 makes clear its deference to criminal law. The entirety of federal criminal law enforcement is unaffected by Section 230.[62] So is all of state law that is consistent with the policy of Section 230.[63] Still, state law that is inconsistent with the aims of Section 230 is preempted.[64] Why did Congress choose this course? First, and most fundamentally, it is because the essential purpose of Section 230 is to establish a uniform federal policy, applicable across the internet, that avoids results such as the state court decision in Prodigy. The internet is the quintessential vehicle of interstate, and indeed international, commerce. Its packet-switched architecture makes it uniquely susceptible to multiple sources of conflicting state and local regulation, since even a message from one cubicle to its neighbor inside the same office can be broken up into pieces and routed via servers in different states. Were every state free to adopt its own policy concerning when an internet platform will be liable for the criminal or tortious conduct of another, not only would compliance become oppressive, but the federal policy itself could quickly be undone. All a state would have to do to defeat the federal policy would be to place platform liability laws in its criminal code. Section 230 would then become a nullity. Congress thus intended Section 230 to establish a uniform federal policy, but one that is entirely consistent with robust enforcement of state criminal and civil law.

[49] Despite the necessary preemption of inconsistent state laws, Section 230 is constructed in such a way that every state prosecutor and every civil litigant can successfully target illegal online activity by properly pleading that the defendant was at least partially involved in the creation of illegal content, or at least the later development of it. In all such cases, Section 230 immunity does not apply. In this respect, statutory form clearly followed function: Congress intended that this legislation would provide no protection for any website, user, or other person or business involved even in part in the creation or development of content that is tortious or criminal. This specific intent is clearly expressed in the definition of “information content provider” in subsection (f)(3) of the statute.[65]

[50] In the two and a half decades that Section 230 has been on the books, there have been hundreds of court decisions interpreting and applying it. It is now firmly established in the case law that Section 230 cannot act as a shield whenever a website is in any way complicit in the creation or development of illegal content. In the landmark en banc decision of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in Fair Housing Council of San Fernando Valley v. Roommates.com,[66] which has since been widely cited and applied in circuits across the United States, it was held that not only do websites lose their immunity when they merely “develop” content created by others, but participation in others’ content creation includes wholly automated features of a website that are coded into its architecture.[67]

[51] There are many examples of courts faithfully applying the plain language of Section 230(f)(3) to hold websites liable for complicity in the creation or development of illegal third-party content. In its 2016 decision in Federal Trade Comm’n v. Leadclick Media, LLC,[68] the Second Circuit Court of Appeals rejected a claim of Section 230 immunity by an internet marketer relying on the fact that it did not create the illegal content at issue, and the content did not appear on its website. The court noted that while this was so, the internet marketer gave advice to the content creators. This made them complicit in the development of the illegal content. As a result, they were not entitled to Section 230 immunity.

[52] In FTC v. Accusearch,[69] the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals held that a website’s mere posting of content that it had no role whatsoever in creating — telephone records of private individuals — constituted “development” of that information, and so deprived it of Section 230 immunity. Even though the content was wholly created by others, the website knowingly transformed what had previously been private information into a publicly available commodity. Such complicity in illegality is what defines “development” of content, as distinguished from its creation.

[53] Other notable examples of this now well-established application of Section 230 are Enigma Software Group v. Bleeping Computer,[70] in which a website was denied immunity despite the fact it did not create the unlawful content at issue, because of an implied agency relationship with an unpaid volunteer who did create it; and Alvi Armani Medical, Inc. v. Hennessey,[71] in which the court found a website to be complicit in content creation because of its alleged knowledge that postings were being made under false identities.

[54] In its 2016 decision in Jane Doe v. Backpage.com,[72] however, the First Circuit Court of Appeals cast itself as an outlier, rejecting the holding in Roommates.com and its progeny. Instead, it held that “claims that a website facilitates illegal conduct through its posting rules necessarily treat the website as a publisher or speaker of content provided by third parties and, thus, are precluded by section 230(c)(1).”[73] This holding completely ignores the definition in subsection (f)(3) of Section 230, which clearly provides that anyone — including a website — can be an “information content provider” if they are “responsible, in whole or in part, for the creation or development” of online content. The broad protection against being treated as a publisher, as is stated clearly in Section 230(c)(1), applies only with respect to online content provided by another information content provider.

[55] Despite the fact that the First Circuit holding was out of step with other decisional law in this respect, the Backpage litigation gained great notoriety because the Backpage.com website was widely reported to be criminally involved in sex trafficking. The massive media attention to the case and its apparent unjust result gave rise to the notion that Section 230 routinely operates as a shield against actual wrongdoing by websites. In fact, the opposite is the case: other courts since 2016 have uniformly followed the Roommates precedent, and increasingly have expanded the circumstances in which they are willing to find websites complicit in the creation or development of illegal content provided by their users.[74]

[56] Ironically, the actual facts in the Backpage case were a Technicolor display of complicity in the development of illegal content. Backpage knowingly concealed evidence of criminality by systematically editing its adult ads; it coached its users on how to post “clean” ads for illegal transactions; it deliberately edited ads in order to facilitate prostitution; it prescribed the language used in ads for prostitution; and it moderated content on the site not to remove ads for prostitution, but to camouflage them. It is difficult to imagine a clearer case of complicity “in part, for the creation or development” of illegal content.[75] Unfortunately, the First Circuit found that the Jane Doe plaintiffs, “whatever their reasons might be,” had “chosen to ignore” any allegation of Backpage’s content creation. Instead, the court said, the argument that Backpage was an “information content provider” under Section 230 was “forsworn” by the plaintiffs, both in the district court and on appeal. The court regretted that it could not interject that issue itself.[76]

[57] Happily, even within the First Circuit, this mistake has now been rectified. In the 2018 decision in Doe v. Backpage.com,[77] a re-pleading of the original claims by three new Jane Doe plaintiffs, the court held that allegations that Backpage changed the wording of third-party advertisements on its site was sufficient to make it an information content provider, and thus ineligible for Section 230 immunity. Much heartache could have been avoided had the facts concerning Backpage’s complicity been sufficiently pleaded in the original case, and had the court reached this sensible and clearly correct decision on the law in the first place.

[58] Equally misguided as the notion that Section 230 must shield wrongdoing are assertions that Section 230 was never meant to apply to e-commerce.[78] To the contrary, removing the threat to e-commerce represented by the Prodigy decision was an essential purpose in the development and enactment of Section 230. When Section 230 became law in 1996, user-generated content was already ubiquitous on the internet. The creativity being demonstrated by websites and users alike made it clear that online shopping was an enormously consumer-friendly use of the new technology. Features such as CompuServe’s “electronic mall” and Prodigy’s mail-order stores were instantly popular. So too were messaging and email, which in Prodigy’s case came with per-message transaction fees. Web businesses such as CheckFree demonstrated as far back as 1996 that online bill payment was not only feasible but convenient. Prodigy, America Online, and the fledgling Microsoft Network included features we know today as content delivery, each with a different payment system. Both Rep. Wyden and I had all of these iterations of internet commerce in mind when we drafted our legislation. We made this plain during our extensive outreach to members of both the House and Senate during 1995 and 1996.

[59] Yet another misconception about the coverage of Section 230, often heard, is that it created one rule for online activity and a different rule for the same activity conducted offline.[79] To the contrary, Section 230 operates to ensure that like activities are always treated alike under the law. When Section 230 was written, just as now, each of the commercial applications flourishing online had an analog in the offline world, where each had its own attendant legal responsibilities. Newspapers could be liable for defamation. Banks and brokers could be held responsible for failing to know their customers. Advertisers were responsible under the Federal Trade Commission Act and state consumer laws for ensuring their content was not deceptive and unfair. Merchandisers could be held liable for negligence and breach of warranty, and in some cases even subjected to strict liability for defective products.

[60] In writing Section 230, Rep. Wyden and I, and ultimately the entire Congress, decided that these legal rules should continue to apply on the internet just as in the offline world. Every business, whether operating through its online facility or through a brick-and-mortar facility, would continue to be responsible for all of its own legal obligations. What Section 230 added to the general body of law was the principle that an individual or entity operating a website should not, in addition to its own legal responsibilities, be required to monitor all of the content created by third parties and thereby become derivatively liable for the illegal acts of others. Congress recognized that to require otherwise would jeopardize the quintessential function of the internet: permitting millions of people around the world to communicate simultaneously and instantaneously. Congress wished to “embrace” and “welcome” this not only for its commercial potential but also for “the opportunity for education and political discourse that it offers for all of us.”[80] The result is that websites are protected from liability for user-created content, but only if they are wholly uninvolved in the creation or development of that content. Today, virtually every substantial brick-and-mortar business of any kind, from newspapers to retailers to manufacturers to service providers, has an internet presence as well through which it conducts e-commerce. The same is true for the vast majority of even the smallest businesses.[81] The same legal rules and responsibilities apply across the board to all.

[61] It is worth debunking three other “creation myths” about Section 230. The first is that Section 230 was conceived as a way to protect an infant industry.[82] According to this narrative, in the early days of the internet, Congress decided that small startups needed protection. Now that the internet has matured, it is argued, the need for such protection no longer exists; Section 230 is no longer necessary. As co-author of the legislation, I can verify that this is an entirely fictitious narrative. Far from wishing to offer protection to an infant industry, our legislative aim was to recognize the sheer implausibility of requiring each website to monitor all of the user-created content that crossed its portal each day. In the 1990s, when internet traffic was measured in the tens of millions, this problem was already apparent. Today, in the third decade of the 21st century, the enormous growth in the volume of traffic on websites has made the potential consequences of publisher liability far graver. Section 230 is needed for this purpose now, more than ever.

[62] The second “creation myth” is that Section 230 was adopted as a special favor to the tech industry, which lobbied for it on Capitol Hill and managed to wheedle it out of Congress by working the system.[83] The reality is far different. In the mid-1990s, internet commerce had very little presence in Washington. When I was moved to draft legislation to remedy the Prodigy decision, it was based on my reading news reports of the case. No company or lobbyist contacted me. Throughout the process, Rep. Wyden and I heard not at all from the leading internet services of the day. This included both Prodigy and CompuServe, whose lawsuits inspired my legislation. As a result, our discussions of the proposed legislation with our colleagues in the House and Senate were unburdened by importunities from businesses seeking to gain a regulatory advantage over their competitors. I willingly concede that this was, therefore, a unique experience in my lawmaking career. It is also the opposite of what Congress should expect if it undertakes to amend Section 230, given that today millions of websites and hundreds of millions of internet users have an identifiable stake in the outcome.

[63] The final creation myth is that Section 230 was part of a grand bargain with Senator James Exon (D-NE), in which his Communications Decency Act aimed at pornography was paired with the Cox-Wyden bill, the Internet Freedom and Family Empowerment Act, aimed at greenlighting websites to adopt content moderation policies without fear of liability.[84] The claim now being made is that the two bills were actually like legislative epoxy, with one part requiring the other. And since the Exon legislation was subsequently invalidated as unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court, so the argument goes, Section 230 should not be allowed to stand on its own. In fact, this revisionist argument contends, the primary congressional purpose back in 1996 was not to give internet platforms limited immunity from liability as Section 230 does. Rather, the most important part of the imagined “package” was Senator Exon’s radical idea of imposing stringent liability on websites for the illegal acts of others[85] — an idea that Exon himself backed away from before his amendment was actually passed.[86] The logical conclusion of this argument is that, the Supreme Court having thrown out the Exon bathwater, the Section 230 baby should now be thrown out along with it.

[64] The reality, however, is far different than this revisionist history would have it. The facts that the Cox-Wyden bill was designed as an alternative to the Exon approach; that the Communications Decency Act was uniformly criticized during the House debate by members from both parties, while not a single Representative spoke in support of it; that the vote in favor of the Cox-Wyden amendment was 420-4; and that the House version of the Telecommunications Act included the Cox-Wyden amendment while pointedly excluding the Exon amendment — all speak loudly to this point. The Communications Decency Act was never a necessary counterpart to Section 230.

VI. CONCLUSION

[65] This history is especially relevant today, as Americans for whom the internet is now a ubiquitous feature of daily life grapple with the same issues of content moderation, privacy, free speech, and the dark side of cyberspace that challenged policy makers in 1995-96. In the current 116th Congress, there is a noticeable resurgence of support for government regulation of content, with all that portends.

[66] Today’s “techlash” and neo-regulatory resurgence is fueled by the same passions and concerns as it was 25 years ago, including protecting children, as well as the more recent trend toward restricting speech that may be offensive to some segments of adults. In June 2020, The New York Times fired its opinion editor, ostensibly for publishing an op-ed by a sitting Republican U.S. senator on a critical issue of the day.[87] Supporters of President Donald Trump complained when Twitter moved to fact-check and contextualize his tweets,[88] while progressives complained that Facebook was not doing this.[89] Senators and representatives are writing legislation that would settle these arguments through force of law rather than private ordering, including legislation to walk back the now prosaically-named Section 230.

[67] In these legislative debates, James Exon’s misguided handiwork is often romanticized by the new wave of speech regulators. Recalling its deep flaws, myriad unintended consequences, and dangerous threats to both free speech and the functioning of the internet is a worthwhile reality check.

[68] Not only is the notion that the Communications Decency Act and Section 230 were conceived together completely wrong, but so too is the idea that the Exon approach enjoyed lasting congressional support. By the time the Telecommunications Act completed its tortuous legislative journey, support for the Communications Decency Act had dwindled even in the Senate, as senators came to understand the mismatch between problem and solution that the bill represented. With the exception of its most passionate supporters, few tears were shed for the Exon legislation at its final demise in 1997. James Exon had retired from the Senate even before his law was declared unconstitutional, leaving few behind him willing to carry the torch. His colleagues made no effort to “fix” and replace the Communications Decency Act, after it was unanimously struck down by the Supreme Court.

[69] Meanwhile Section 230, originally introduced in the House as a freestanding bill, H.R. 1978, in June 1995, stands on its own, now as then. Its premise of imposing liability on criminals and tortfeasors for their own wrongful conduct, rather than shifting that liability to third parties, operates independently of (and indeed, in opposition to) Senator Exon’s approach that would directly interfere with the essential functioning of the internet.

[70] In the final analysis, it is useful to place this legislative history in contemporary context. Imagine returning to a world without Section 230, as some today are urging. In this alternative world, websites and internet platforms of all kinds would face enormous potential liability for hosting content created by others. They would have a powerful incentive to limit that exposure, which they could do in one of two ways. They could strictly limit user-generated content, or even eliminate it altogether; or they could adopt the “anything goes” model through which CompuServe originally escaped liability before Section 230 existed. We would all be very much worse off were this to happen. Without Section 230’s clear limitation on liability it is difficult to imagine that most of the online services on which we rely every day would even exist in anything like their current form. While courts will continue to grapple with the challenges of applying Section 230 to the ever-changing landscape of the 21st century internet, hewing to its fundamental principles and purposes will be a far wiser course for policy makers than opening a Pandora’s box of unintended consequences that upending the law would unleash.

[1] 47 U.S.C. § 230 (“Section 230”).

[2] Stratton Oakmont v. Prodigy Servs. Co., 1995 N.Y. Misc. LEXIS 229, 1995 WL 323710, 23 Media L. Rep. 1794 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. May 24, 1995).

[3] See the discussion of Jane Doe v. Backpage.com in Part V, infra.

[4] See, e.g., S. 3398, the EARN IT Act; S. 1914, the Ending Support for Internet Censorship Act; H. R. 4027, the Stop the Censorship Act; S. 3983, the Limiting Section 230 Immunity to Good Samaritans Act; S.4062, Stopping Big Tech’s Censorship Act; and S. 4066, the ‘‘Platform Accountability and Consumer Transparency Act.”

[5] https://www.aclu.org/issues/free-speech/internet-speech/communications-decency-act-section-230

[6] Kate Klonick, The New Governors: The People, Rules, and Processes Governing Online Speech, 131 Harv. L. Rev. 1598, 1625-30 (2018); “What Is Content Moderation and Why Companies Need It,” Bridged, September 3, 2019, https://bridged.co/blog/what-is-content-moderation-why-companies-need-it/

[7] Derek E. Bambauer, “How Section 230 Reform Endangers Internet Free Speech,” Tech Stream, Brookings Institution, July 1, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/techstream/how-section-230-reform-endangers-internet-free-speech/ ; “The Fight Over Section 230—and the Internet as We Know It,” Wired, August 13, 2019, https://www.wired.com/story/fight-over-section-230-internet-as-we-know-it/

[8] Dawn Carla Nunziato, From Town Square to Twittersphere: The Public Forum Doctrine Goes Digital, 25 B.U. J.Sci. & Tech.L. 1 (2019).

[9] Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501 (1946); Food Employees Local 590 v. Logan Valley Plaza, Inc., 391 U.S. 308 (1968); Petersen v. Talisman Sugar Corp., 478 F.2d 73 (5th Cir. 1973); Pruneyard Shopping Center v. Robins, 447 U.S. 74 (1980).

[10] 47 U.S. Code § 230(c)(2)(A).

[11] Department of Justice’s Review of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, https://www.justice.gov/ag/department-justice-s-review-section-230-communications-decency-act-1996?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery ; “Justice Department Wants to Chip Away at Section 230,” Protocol, June 18, 2020, https://www.protocol.com/justice-department-section-230-proposal

[12] “Legislation Would Make Tech Firms Accountable for Child Porn,” New York Times, March 6, 2020, B7; Andrew M. Sevanian, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act: A “Good Samaritan’ Law Without the Requirement of Acting as a ‘Good Samaritan,” 21 UCLA Ent. L. Rev. 121 (2014).

[13] “Pelosi Says Facebook Enabled Russian Interference in Election,” New York Times, May 30, 2019, B4.

[14] “Legal Shield for Social Media Is Targeted by Trump,” New York Times, May 28, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/28/business/section-230-internet-speech.html ; “What is Section 230 and Why Does Donald Trump Want to Change It?,” MIT Technology Review, August 13, 2019, https://www.technologyreview.com/2019/08/13/610/section-230-law-moderation-social-media-content-bias/

[15] “Section 230 Is the Internet’s First Amendment. Now Both Republicans and Democrats Want To Take It Away,” Reason, July 29, 2019, https://reason.com/2019/07/29/section-230-is-the-internets-first-amendment-now-both-republicans-and-democrats-want-to-take-it-away/

[16] Josh Hawley, “The True History of Section 230,” https://www.hawley.senate.gov/sites/default/files/2020-06/true-history-section-230.pdf

[17] Communications Decency Act, S. 314, 104th Cong., 1st Sess. (February 2, 1995)(“CDA”).

[18] 104th Cong., 1st Sess., 141 Cong. Rec. Pt. 11, 16007 (June 14, 1995)(remarks of Sen. Exon).

[19] Id. at 16007-08 (June 14, 1995).

[20] CDA §2.

[21] Robert Cannon, The Legislative History of Senator Exon’s Communications Decency Act: Regulating Barbarians on the Information Superhighway, 49 Fed. Comm. L.J. 51, 71-72 n.103.

[22] “Cyber Liberties Alert from the ACLU,” March 23, 1995, http://besser.tsoa.nyu.edu/impact/w95/RN/mar24news/Merc-news-cdaupdate.html When the Exon bill was offered as an amendment to the Telecommunications Act in the Commerce Committee, Chairman Pressler first moved to table it; when the motion to table was defeated, the amendment was approved on a voice vote.

[23] 104th Cong., 1st Sess., 141 Cong. Rec. Pt. 11, 16010 (June 14, 1995)(remarks of Sen. Leahy).

[24] 104th Cong., 1st Sess., 141 Cong. Rec. Pt. 11, 15503-04 (June 9, 1995) (remarks of Sen. Exon, describing his “blue book”).

[25] 104th Cong., 1st Sess., 141 Cong. Rec. Pt. 11, 16009 (June 14, 1995)(remarks of Sen. Exon).

[26] Id. at 16007. The amendment was intended to address criticisms that the Communications Decency Act was overbroad. It provided a narrow defense in cases where the defendant “solely” provides internet access—thereby continuing to expose all websites hosting user-created content to uncertain criminal liability.

[27] S. 652, Telecommunications Competition and Deregulation Act of 1995 (March 30, 1995).

[28] 104th Cong., 1st Sess., 141 Cong. Rec. Pt. 11, 16026 (June 14, 1995).

[29] Robert Cannon, The Legislative History of Senator Exon’s Communications Decency Act: Regulating Barbarians on the Information Superhighway, 49 Fed. Comm. L.J. 51, 71-72 and n.103.

[30] Id.

[31] “Cyberporn—On a Screen Near You,” Time, July 3, 1995, 38.

[32] Internet Freedom and Family Empowerment Act, H.R. 1978, 104th Cong., 1st Sess. (June 30, 1995)(“IFFEA”).

[33] Conor Clark, “How the Wolf of Wall Street Created the Internet,” January 7, 2014, https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2014/01/the-wolf-of-wall-street-and-the-stratton-oakmont-ruling-that-helped-write-the-rules-for-the-internet.html

[34] Cubby, Inc. v. CompuServe, Inc., 776 F. Supp. 135 (S.D.N.Y. 1991).

[35] Stratton Oakmont v. Prodigy Servs. Co., 1995 N.Y. Misc. LEXIS 229, 1995 WL 323710, 23 Media L. Rep. 1794 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. May 24, 1995).

[36] See IFFEA § 2.

[37] “Gingrich Opposes Smut Rule for Internet,” New York Times, June 22, 1995, A20.

[38] 104th Cong., 2nd Sess., 142 Cong. Rec. H1173 (Daily Ed. Feb. 1, 1996) (statement of Rep. Pelosi).

[39] 104th Cong., 1st Sess., 141 Cong. Rec. Part 16, 22044-054 (August 4, 1995).

[40] Id. at 22046 (remarks of Rep. Lofgren).

[41] Id. (remarks of Rep. Goodlatte).

[42] Id. at 22054.

[43] The Communications Act of 1995, H.R.1555, was approved in the House by a vote of 305-117 on August 4, 1995. Id. at 22084.

[44] Senator Patrick Leahy, a leading proponent of the Cox-Wyden amendment and opponent of Senator Exon’s Communications Decency Act, had previously warned against this logically inconsistent approach. See Comm. Daily Notebook, November 13, 1995, at 6 (reporting Leahy’s concern that the “conference panel would take ‘the easy compromise’” by including both Exon and Cox-Wyden in the Conference Report).

[45] https://clintonwhitehouse4.archives.gov/WH/EOP/OP/telecom/signing.html

[46] https://www.c-span.org/video/?69814-1/telecommunications-bill-signing

[47] ACLU v. Reno, 929 F. Supp. 824 (E.D. Pa. 1996); Shea v. Reno, 930 F.Supp. 916 (S.D.N.Y. 1996); Apollomedia Corp. v. Reno, No. 97-346 (N.D. CA. 1996).

[48] Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union, 521 U.S. 844 (1997).

[49] Id. at 874.

[50] Id. at 858 n.24.

[51] Id. at 877 n.44.

[52] Id. at 880.

[53] Id. at 882.

[54] “At Least 34 Dead, Half a Million Without Power After Storms, Tornadoes Batter South,” ABC News, April 14, 2020, https://abcnews.go.com/US/dead-half-million-power-storms-batter-south/story?id=70113106

[55] “How to Teach Yourself How to Do Almost Anything: Web Sites Help Users Find Instructional Videos,” Wall Street Journal, May 7, 2008, D10.

[56] “The COVID-19 Pandemic Has Changed Education Forever. This Is How,” World Economic Forum, April 29, 2020, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/coronavirus-education-global-covid19-online-digital-learning/

[57] Gaurav Kumar, 50 Stats About 9 Emerging Content Marketing Trends for 2016, SEMRUSH BLOG (December 29, 2015), https://www.semrush.com/blog/50-stats-about-9-emerging-content-marketing-trends-for-2016

[58] Yin Wu, “What Are Some Interesting Statistics About Online Consumer Reviews?,” DR4WARD.COM (March 26, 2013), http://www.dr4ward.com/dr4ward/2013/03/what-are-some-interesting-statistics-about-online-consumer-reviews-infographic.html

[59] Kimberlee Morrison, “Why Consumers Share User-Generated Content,” Adweek (May 17, 2016), http://www.adweek.com/digital/why-consumers-share-user-generated-content-infographic

[60] Jarrod Sadulski, “Why Social Media Plays an Important Role in Law Enforcement,” In Public Safety, March 9, 2018, https://inpublicsafety.com/2018/03/why-social-media-plays-an-important-role-in-law-enforcement/

[61] See, e.g., “These Cities Replaced Cops With Social Workers, Medics, and People Without Guns,” Vice, June 14, 2020, https://www.vice.com/en_au/article/y3zpqm/these-cities-replaced-cops-with-social-workers-medics-and-people-without-guns; see also “How You Can Help Minneapolis-St. Paul Rebuild and Support Social Justice Initiatives,” Fox 9 KMSP, May 30, 2020, https://www.fox9.com/news/how-you-can-help-minneapolis-st-paul-rebuild-and-support-social-justice-initiatives

[62] 47 U.S.C. § 230(e)(1) provides: “No effect on criminal law. Nothing in this section shall be construed to impair the enforcement of section 223 or 231 of this title, chapter 71 (relating to obscenity) or 110 (relating to sexual exploitation of children) of title 18, or any other Federal criminal statute” (emphasis added).

[63] 47 U.S.C. § 230(e)(3) provides: “State law. Nothing in this section shall be construed to prevent any State from enforcing any State law that is consistent with this section” (emphasis added).

[64] 47 U.S.C. § 230(e)(3) further provides: “No cause of action may be brought and no liability may be imposed under any State or local law that is inconsistent with this section.”

[65] 47 U.S.C. § 230(f)(3) provides: “Information content provider. The term “information content provider” means any person or entity that is responsible, in whole or in part, for the creation or development of information provided through the Internet or any other interactive computer service” (emphasis added).

[66] 521 F.3d 1157 (9th Cir. 2008).

[67] Id. at 1168.

[68] 838 F.3d 158 (2d Cir. 2016).

[69] 570 F.3d1187, 1197 (10th Cir. 2009).

[70] 194 F.Supp.3d 263 (2016).

[71] 629 F. Supp. 2d 1302 (S.D. Fla. 2008).

[72] Jane Doe No. 1 v. Backpage.com, LLC, 817 F.3d 12 (1st Cir. 2016).

[73] Id. at 22 (emphasis added).

[74] J.S. v. Village Voice Media Holdings, LLC, 184 Wash. 2d 95, 359 P.3d 714 (2015), is a representative example, also involving Backpage.com. Stating the test of Section 230, the court held that Backpage would not be a content creator under § 230(f)(3) if it “merely hosted the advertisements.” But if “Backpage also helped develop the content of those advertisements,” then “Backpage is not protected by CDA immunity.” Id. at 717. As in Roommates.com, where the website itself was designed so as to yield illegal content, the court cited the allegations that Backpage’s “content requirements are specifically designed to control the nature and context of those advertisements,” so that they can be used for “the trafficking of children.” Moreover, the complaint alleged that Backpage has a “substantial role in creating the content and context of the advertisements on its website.” In holding that, on the basis of the allegations in the complaint, Backpage was a content creator, the court expressly followed the Roommates holding, and the clear language of Section 230 itself. “A website operator,” the court concluded, “can be both a service provider and a content provider,” id. at 717-18, and when it is a content provider it no longer enjoys Section 230 protection from liability.

[75] These facts are laid out in considerable detail in the 2017 Staff Report of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations concerning Backpage.com, https://www.hsgac.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Backpage%20Report%202017.01.10%20FINAL.pdf

[76] Jane Doe No. 1 v. Backpage.com, LLC, 817 F.3d 12 (1st Cir. 2016), 19 n.4.

[77] Doe No. 1 v. Backpage, 2018 WL 1542056 (D. Mass. March 29, 2018).

[78] See, e.g., Review of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, U.S. Department of Justice, June 17, 2020 (“The internet has changed dramatically in the 25 years since Section 230’s enactment in ways that no one, including the drafters of Section 230, could have predicted …. Platforms no longer function as simple forums for posting third-party content, but instead … engage in commerce”); Cathy Gellis, “The Third Circuit Joins The Ninth In Excluding E-Commerce Platforms From Section 230’s Protection,” Techdirt, July 15, 2019, https://www.techdirt.com/articles/20190709/13525442547/third-circuit-joins-ninth-excluding-e-commerce-platforms-section-230s-protection.shtml

[79] See, e.g., Chris Reed, Online and Offline Equivalence: Aspiration and Achievement, Int’l J.L.& Info. Tech. 248 (Autumn 2010), 252 and n.22 (characterizing Section 230 as enforcing “rules which apply only online…. [T]he result may well have been to favour online publishing over offline in some circumstances”).

[80] 104th Cong., 1st Sess., 141 Cong. Rec. Part 16, 22045 (August 4, 1995)(remarks of Rep. Cox).

[81] About two-thirds (64%) of U.S. small businesses have websites, while nearly a third (29%) plan to begin using websites for the first time in 2020. Sandeep Rathore, “29% of Small Businesses Will Start a Website This Year,” Small Business News, February 6, 2020, https://smallbiztrends.com/2020/02/2020-small-business-marketing-statistics.html

[82] See, e.g., Michael L. Rustad, The Role of Cybertorts in Internet Governance, The Comparative Law Yearbook of International Business, ed. Dennis Campbell (2018), 391, 411 (“Congress enacted Section 230 … as a subsidy to the infant industry of the Internet”); Mark Schultz, “Is There Internet Life After 30?,” The Hill, Congress Blog, August 23, 2019, https://thehill.com/blogs/congress-blog/technology/458620-is-there-internet-life-after-thirty (Section 230 was intended as an “exception for an infant industry”); see generally Marc J. Melitz, When and How Should Infant Industries Be Protected?, 66 J. of Int’l. Econ. 177–196 (2005).

[83] See, e.g., Richard Hill, “Trump and CDA Section 230: The End of an Internet Exception?,” Bot Populi, July 2, 2020 (“Internet service providers lobbied to have a special law passed that would allow them to monitor content without becoming fully liable for what they published. The lobbying was successful and led to the US Congress adopting Section 230”), https://botpopuli.net/trump-and-cda-section-230-the-end-of-an-internet-exception ; “Section 230 Was Supposed to Make the Internet a Better Place. It Failed,” Bloomberg Businessweek, August 7, 2019 (positing that Section 230 was the result of “influential [lobbying] of technophobes on Capitol Hill” that included “organizing protests”).

[84] See, e.g., Josh Hawley, “The True History of Section 230,” https://www.hawley.senate.gov/sites/default/files/2020-06/true-history-section-230.pdf

[85] Id.

[86] In an effort to address criticisms from objecting senators, the final version of the Exon amendment, as it was incorporated into the Telecommunications Act of 1996, lessened the criminal exposure of websites and online service providers through the addition of four new defenses. This caused the Clinton administration to complain that the revised Exon legislation now defeated its own purpose by actually making criminal prosecution of obscenity more difficult. It “would undermine the ability of the Department of Justice to prosecute an on-line service provider,” the Justice Department opined, “even though it knowingly profits from the distribution of obscenity or child pornography.” 104th Cong., 1st Sess., 141 Cong. Rec. Pt. 11, 16023 (June 14, 1995)(letter from Kent Markus, Acting Assistant Attorney General, Department of Justice, to Senator Patrick Leahy).

[87] “The Times’s Opinion Editor Resigns Over Controversy,” New York Times, June 8, 2020, B1 (quoting publisher A. G. Sulzberger’s pronouncement that “Both of us concluded that James [Bennet] would not be able to lead the team”).

[88] Brad Polumbo, “Twitter Sets Itself Up for Failure with ‘Fact-check’ on Trump Tweet,” Washington Examiner, May 27, 2020, https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/opinion/twitters-fact-check-on-trump-tweet-sets-itself-up-for-failure

[89] “Zuckerberg and Trump: Uneasy Ties,” New York Times, June 22, 2020, B1.