By: Rachel Whalen

“In 2019, healthcare consumers continue to demand greater transparency, accessibility and personalization.”[1] In this increasingly digital age, incorporating Health information technology (“Health IT”) into the health industry is very important. Health IT is “the exchange of health information in an electronic environment.”[2] A variety of electronic methods are used, such as computerized disease registries, electronic record systems (“EHRs”), and electronic prescribing.[3] Health care systems are implementing Health IT to mange health information and care for individuals and groups.[4]

The widespread use of Health IT improves quality of care, prevents medical error, reduces costs, and decreases inefficiencies.[5] Communication between health care providers and patients is better than ever before thanks to advances in securing Health IT networks.[6] More accurate EHRs can follow a patient to different health care providers. Apps and increased access to information can give patients more control over their care. This has improved the ability to help patients meet their health goals and to give the patients more control over their health.[7] Health IT’s merging of technology with healthcare has improved access to healthcare and the consistency of care.[8]

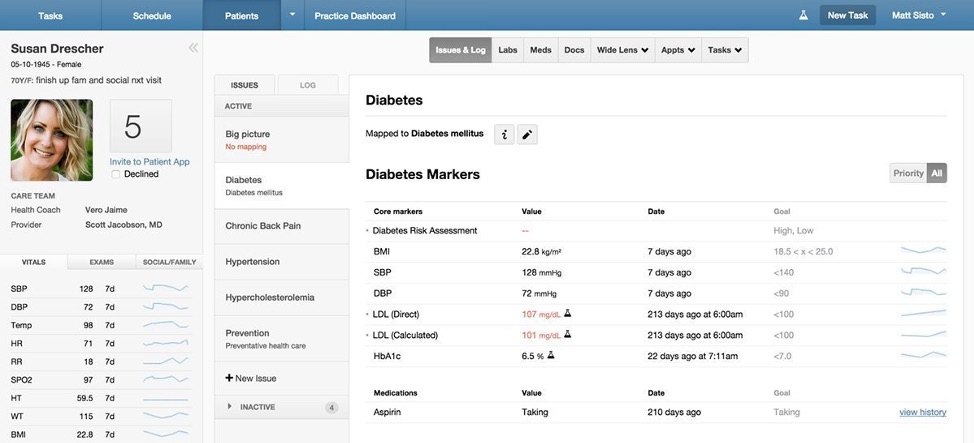

There are several different components of Health IT that add complexity to the system which does not exist in other communication technologies. The central component of Health IT infrastructure is the EHR.[9] These EHRs, or electronic medical records (“EMRs”), contain all of a person’s official health record in a digital format.[10] These digital records can be viewed even when the doctor’s office is closed, providing greater access to a person’s health information.[11] EHRs can also be used to share information between multiple healthcare providers and agencies within the healthcare system.[12] This makes it easier for doctors to share information with specialists and ensure consistent care.[13] Health IT also works outside of the healthcare system with personal health records (“PHRs”). PHRs are self-maintained health records controlled by the patient themself.[14] PHRs can be used to track doctor visits and treatments, as well as activities outside of the doctor’s office.[15] Patients can track their eating and exercise habits, as well as their blood pressure, heartbeat, and other medical parameters.[16] PHRs may even record medications and prescriptions if the PHR is linked to the doctor’s electronic prescribing (“E-prescribing”).[17] E-prescribing connects the doctors directly to the pharmacy, so no paper prescriptions are lost or misread.[18] This gives patients wider access to pharmaceuticals without having to bring paper prescriptions with them.[19]

Developments in Health IT have improved the popularity and access to health records among patients. Smartphones and apps have encouraged patients to use PHRs and have helped patients become more comfortable with their digital health information.[20] Health care providers have also increasingly implemented and used patient portals due to more consumer-friendly designs. Apps and patient portals were clunky and limited near the beginning of Health IT, but modern systems provide more options and customization options.[21] Patient portals used to only provide information of upcoming appointments and perhaps some test results.[22] Now, patient portals are used to download health records, securely communicate with physicians, pay bills, check services, check insurance coverage, and order prescriptions.[23] These Health IT services grant patients more access to and control over their health information and health care treatment.

In addition to individual records, Health IT has established a health information exchange (“HIE”).[24] Health care providers must manage a mountain of patient health information. Thus, there has been a consequential increase in the importance of data analytics.[25] HIEs are systems developed by groups of health care providers to share data between Health IT networks.[26] These shared systems and agreements between health care providers not only allow for better communication and consistent care, but also provide a large database of health information to analyze the health of communities as a whole.[27] Academic researchers can use the shared health information to develop new medical treatments and pharmaceuticals.[28] This plethora of information can be used to manage population health goals and research health trends.[29]

Unfortunately, this amount of information is very difficult to manage, which again increases the reliance on data analytics to find relevant files.[30] This is where other Health IT technologies come in, specifically picture archiving and communication systems (“PACs”) and vendor-neutral archives (“VNAs”). While images have been of most importance to radiologists, other specialties, such as cardiology and neurology, are also producing a large amount of clinical images.[31] PACs and VNAs are widely used to store and manage patient medical images and, in some cases, have even been integrated into shared systems between facilities and health providers.[32] Some Health IT systems even use artificial intelligence (“AI”) to sort and manage files.[33]

In addition to the advantages discussed above, the ability to quickly share accurate information, called “interoperability,” could be the difference between life and death for a patient. Health IT tools improve the necessary cooperation between health care providers for improved patient care and lower healthcare costs.[34] The “interoperability” and rapid information sharing provided by Health IT tools provides health care providers with the most updated information and can even provide patients with immediate access to their health records. Health care providers need personal information and basic medical history, which requires patients to provide repetitive information and paperwork. Interoperability information sharing provides that basic information to health care providers without the excess paperwork and allows for faster treatment. Similarly, health care providers have access to test results from other facilities, which prevents unnecessary tests and improves consistency of treatment. Consistent treatment is further aided by follow up treatment with alerts and reminders for ongoing health conditions, appointments, and medications.[35]

Digital records protect patient information in the event of emergency by allowing recovery of documents, as well as constant access to health records, which can follow patients to any provider, regardless of location. This allows for consistent treatment. The use of electronic systems also provides the ability to encrypt information so only authorized personnel have access. Electronic information can also be tracked to record who accesses the information and when they accessed it. Several of these safety advantages are required by the Federal Government. For example, certified Health IT systems are required to designate professionals and others, to limit access to information, so as to manage care effectively.[36]

Strict government regulations limit Health IT due to the amount of confidential information contained in the health information managed by Health IT.[37] Privacy and security is a top priority for the Federal Government as well as patients and health care providers.[38] Medical records can commonly contain the most intimate details of a patient’s life.[39] These files document physical health, mental health, behavioral issues, family information including child care relationships, and financial status.[40] Health care providers need all of this sensitive information to properly treat patients, but a breach of that information could cause innumerable harms to the patients.[41] Therefore, patients are guaranteed clearly defined rights to the privacy of their health information, including electronic health information.[42]

Health care and technology touch on every aspect of our lives. Ever since the computer was invented, various methods have been implemented to improve the efficiency and access of health care incorporation.[43] From EHRs to electronic prescriptions, Health IT has been connecting vital information for patients and health care providers.[44] There are still some issues and miscommunications within the systems, but Health IT will improve as technology improves, providing crucial information and technical support to the health care industry.

[1] Ashley Brooks, What Is Health Information Technology? Exploring the Cutting Edge of Our Healthcare System, Rasmussen C. Health Sci. Blog (June 10, 2019), https://www.rasmussen.edu/degrees/health-sciences/blog/what-is-health-information-technology/ (quoting Patrick Gauthier, director of healthcare solutions at Advocates for Human Potential, Inc.).

[2] Health Information Technology Integration, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, https://www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr/tools/health-it/index.html (last visited Apr. 15, 2020).

[3] See id.

[4] See id.

[5] See Department of Health and Human Services, Health Information Technology, Health Information Privacy, https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/health-information-technology/index.html (last visited Apr. 15, 2020).

[6] See Brooks, supra note 1.

[7] See id.

[8] See id.

[9] See Margaret Rouse, Health IT (health information technology), SearchHealthIT (June 2018), https://searchhealthit.techtarget.com/definition/Health-IT-information-technology.

[10] See id.

[11] See Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, Health IT: Advancing America’s Health Care, https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/health-information-technology-fact-sheet.pdf (last visited Apr. 15, 2020) [hereinafter “ONC”].

[12] See Rouse, supra note 9.

[13] See ONC, supra note 11.

[14] See Rouse, supra note 9.

[15] See ONC, supra note 11.

[16] See id.

[17] See id.

[18] See id.

[19] See id.

[20] See Rouse, supra note 9.

[21] See id.

[22] See id.

[23] See id.

[24] See id.

[25] See Rouse, supra note 9.

[26] See id.

[27] See id.

[28] See id.

[29] See id.

[30] See Rouse, supra note 9.

[31] See id.

[32] See id.

[33] See id.

[34] See Brooks, supra note 1.

[35] See ONC, supra note 11.

[36] See id.

[37] See Brooks, supra note 1.

[38] See ONC, supra note 11.

[39] See Institute of Medicine, Beyond the HIPAA Privacy Rule: Enhancing Privacy, Improving Health Through Research (Laura A. Levit & Lawrence O. Gostin eds., 2009).

[40] See id.

[41] See id.

[42] See ONC, supra note 11.

[43] See The History of Healthcare Technology and the Evolution of EHR, VertitechIT (Mar. 11, 2018), https://www.vertitechit.com/history-healthcare-technology/.

[44] See id.

Law firm relationship management has been driven by personal connections and personal relationships. Very little has changed, but the future methods of relationship management will veer away from the personal and move towards more objective and empirical foundations. Data will become a staple in those relationships and will drive which relationships continue and which ones may end.

Law firm relationship management has been driven by personal connections and personal relationships. Very little has changed, but the future methods of relationship management will veer away from the personal and move towards more objective and empirical foundations. Data will become a staple in those relationships and will drive which relationships continue and which ones may end.